The hardship of migration, coupled with the uncertainties about the future in their homeland, has eroded some of the nuances of family life, deeply affecting not just the individual but every family member. These strains generate emotional dynamics that can significantly influence behavior.

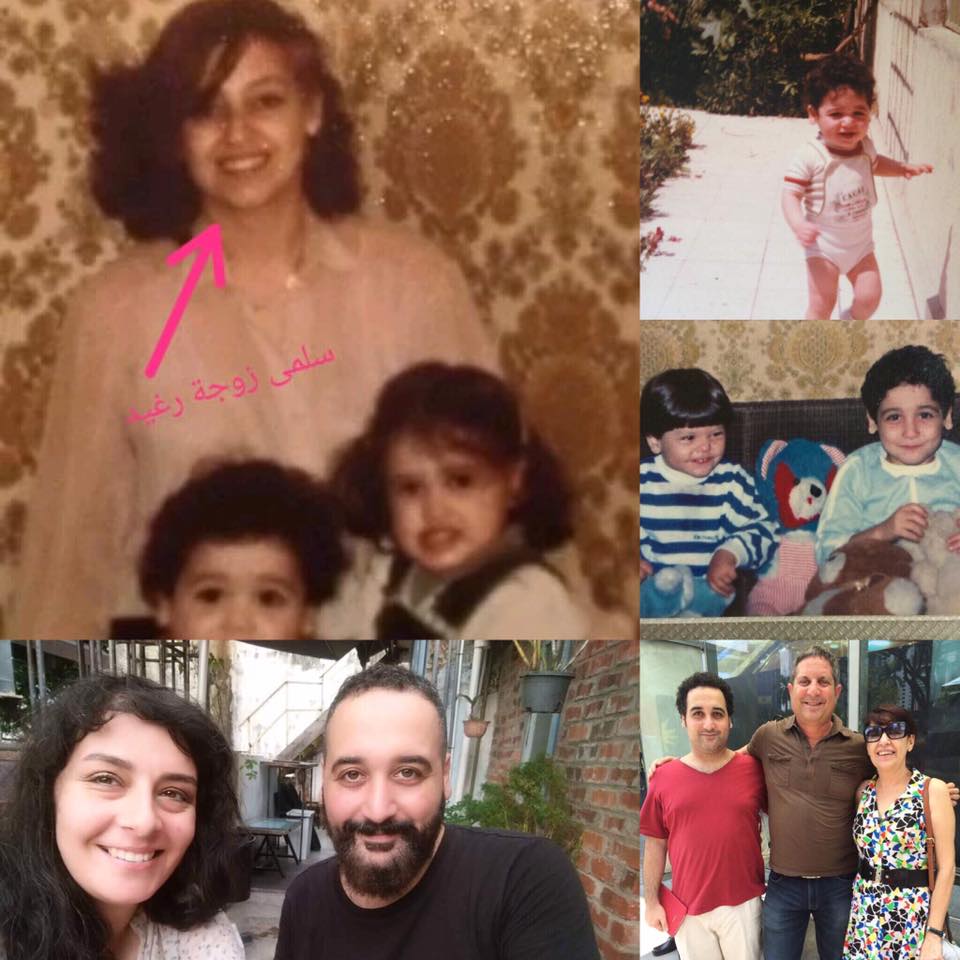

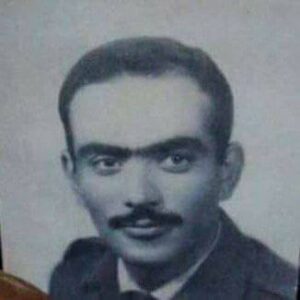

While serving his extended prison sentence, Ragheed became a father. He was incarcerated when his wife was seven months pregnant, he couldn’t meet him until years later due to his incarceration. He first met his son Wael in early 1997, when the boy was fifteen. The emotional weight of their meeting defies easy description, no matter how expansive our vocabulary.

Throughout Ragheed’s imprisonment, his family made a point to visit him in several different detention facilities, including Palmyra, Seydnayah, and Adra. However, their last visit on December 24, 2011, was marked by a harsh condition imposed by prison authorities: Ragheed had to don the penal uniform to receive visitors, a stipulation he refused, thus resulting in the suspension of family visits.

After the Syrian revolution started, the adversity faced by Ragheed’s family intensified. In 2013, following a threat directed at his son Wael from an anonymous source, labeling him the “son of a traitor,” the family felt compelled to flee Syria. Initially, they took refuge in Egypt for six months before moving to Malaysia, a country that does not require visas for Syrians.

The family’s struggles escalated when Wael’s mother fell severely ill due to environmental pollution and inclement weather. Her condition worsened until she passed away in the hospital, after about a week-long wait for a burial permit.

Now, Wael finds himself caught in a maze of life’s necessities. While he awaits an exit visa to settle in a foreign country with his wife, he remains tied emotionally to his imprisoned father and his homeland, Syria.

#Freedom_to_the_oldest_prisoner_in_the_world_Ragheed_Al-Tatari